On our third day in Geneva, we started the day differently than the two days prior; rather than learn about international governmental collaboration at the UN, we learned about international science collaboration at the CERN.

The CERN, or the Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire, was established in 1954 as a joint scientific venture of European states. The founders of the project hoped to restore Europe’s pre-World War II scientific capacity and foster a sense of collaboration between recently feuding counties. Since then, the organization has grown to 23 member states with numerous international partners.

The organization, originally a nuclear research laboratory, currently focusses on particle physics. Particle physics is concerned with the interactions of particles smaller than the atom scale: these include quarks, leptons, gluons, and bosons. These are the most fundamental building blocks of the universe. Particles of these types typically are unwieldy in a conventional laboratory setting, requiring large scale facilities like the CERN to reproduce them. The CERN uses these particles to simulate the early universe where there was little in the way of the complexity of matter and high levels of energy.

For our tour of the facility, we began with an informational video and lecture led by a physicist who has been with the organization for over 30 years. Here we learned about the history, mission, and work of the organization. The lecturer did have gripes about the content of the prerecorded materials, claiming that its stance on dark matter was incorrect. Following this, we were led on a tour of the facility. The compound that houses the CERN is a system of roughly 1500 buildings that support the operation of 9 particle accelerators, the most famous being the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) – which is responsible for the Nobel award-winning discovery of the Higgs-Boson.

Our first stop was to the computing center where data from experiments are collected, parsed, and analyzed. The nature of particle physics research requires every minutia to be recorded resulting in huge amounts of data – typically in the terabyte range. The data is taken from here and transmitted worldwide so international partners can distribute the load of data analysis. All of this computing has led crucial computing technologies, like touch screens and the world wide web, to be developed at the CERN.

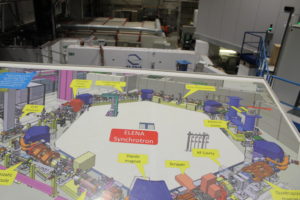

The next, and final, stop on our tour was the antimatter facility. As the name implies, antimatter, the physically opposite component to matter, is studied there. The two experiments we saw were Elena, an antiproton accelerator used to investigate the spectroscopy of antimatter, and G-Bar, a gravity chamber used to study gravitational effects on matter.

Both of the setups looked surprisingly rough, like a mad science lab, rather than clean and sterile as one would expect for such an exact science.

We returned to the gift shop following the tour before finally returning to the conference for the afternoon plenary session.

The delegates focused on remediation and containment of contaminated sites, with discussion from countries reporting on their current work and hopes for comprehensive rules to pass. The most notable comment of the night came from Namibia, who boldly asserted Africa as the best continent on the plant. Though delegates hadn’t agreed on the proper response to earlier comments made, the response to this one was clear: laughter.

Following the long day of all things international, science and government, we returned to our hotel for a much-needed rest.